"May 27th: Useless Knowledge and its Uses"

Between books and the internet, there is a vast repository of useless knowledge. What are some of the useless things you know? Why do you bother remembering these things?

Topics from, A Bookful Blockhead.

Termed by Walter Gilbert, a Nobel-laureate biochemist, an exon is a sequence of DNA that is expressed as protein. This genetic information can be labelled as "useful knowledge", and only makes up about 1.5% of the human genome. These genes code for the proteins that direct and produce a cell's function, but even out of all these genes, many are rarely expressed, and some of these genes are turned off in a significant part of the population. So even among these exons, some of the knowledge is just "somewhat useful", or "perhaps useful once in a blue moon".

Then there are the introns - about a quarter of our DNA. These parts of the gene are inexpressed (generally), though some do play a role (helping in the translation of RNA to protein). Introns provide no information absolutely critical for the cell in the sense of coding for proteins (though some proteins will have a hard time being expressed without them), but nevertheless, we'll call this "trivial knowledge". Stretches of introns are often alternated between exons, and are spliced out before the protein is synthesized.

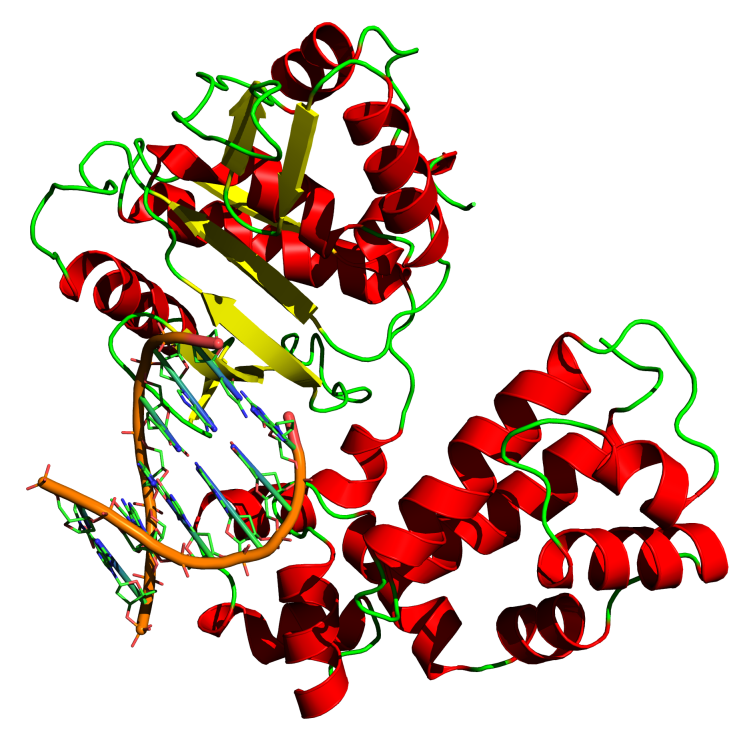

The rest of our DNA, a rather large majority of it, is "intergenic" DNA: between the genes. While some parts of this non-coding DNA does play a role in gene expression, much of it is "useless knowledge", and is also referred to as "junk DNA". There are many reasons, and theories, on why we have so much non-coding DNA, introns included. We often point our fingers at deteriorated ancestral genes, splicing errors, replication errors and repeated sections. But really, the order of the four nucleotides is the only thing setting apart this useless DNA with the few stretches lucky enough to code for something important like DNA polymerase and cytochrome C.

|

| Intergenic DNA dreams of becoming an intron someday. (images courtesy of Wikicommons) |

1) Knowledge is infinite.

There are an infinite number of things to understand, just as there's an infinite number of arrangements of nucleotides. The classic "the more we know, the more we know we don't know". Who knows what mutations will bring us next?

2) The "usefulness" of knowledge is temporal and situational. The usefulness of genes or knowledge comes and goes. The prehensile tail and knowing how to fax a document used to be important at some point in history, but they won't get you much credit nowadays.

3) Knowledge adapts and changes over time, and can behave under Darwinian evolution. Ideas catch on and spread faster than resistance genes in bacteria. Human knowledge, especially scientific concepts, are adapted as we test new hypotheses; the most successful ones are incorporated into existing ideas (or an entirely new set of theories are born!). Ideas can die off, just like genes are lost - normally those that aren't as popular and relevant to a rapidly changing environment. Knowledge can be gained, while knowledge that is no longer useful may be lost.

|

| The countdown begins. 203 days until Beethoven's birthday. (as of post date) |

So the simple answer to the topic-of-the-week is that I don't really see the line between useful and useless knowledge (cop-out answer, perhaps?). One can make a guess at a particular snapshot moment at what is vital and what is trivial, but the usefulness of knowledge like the usefulness of a gene changes as time goes on, and eventually, our knowledge today will be obsolete. Besides, who's to say learning biochemistry is more useful than knowing the date of Beethoven's birthday or the number of keys on the piano? Perhaps it's the latter that will make the daily double difference if I ever make it on Jeopardy! Or if my future employer asks oddly specific music questions during the interview.

I like knowledge, including trivial facts, because I like to learn (who doesn't?). I treat my studies of genetics and my determination to memorize all the countries of the world with the same (or at least similar?) enthusiasm. A vast repository of knowledge is a good thing, like genetic variation. You never know when a gene will come in handy, and it's fun to learn a whole bunch of things, no matter how seemingly useless.

Because knowledge is infinite and our knowledge will become obsolete, all knowledge we know now could be labelled as "useless", but that doesn't seem to keep people from learning things, just like our body continues to use energy to replicate the 98.5% that is non-coding. Since my microscopic DNA polymerase spends its time replicating junk DNA, macroscopic me shall dedicate my life to studying useless knowledge. So what useless knowledge do I know? Just read my blog.

Human DNA polymerase (beta), with a strand of DNA.

You're one of my favourite bloggers right now, yet another interesting and well-written post. :)

ReplyDeleteawesome, yan!

ReplyDeleteAnother delightful post. This bio lover really enjoyed it.

ReplyDelete